Larger Than Life – Domestic Scenes by Carroll Swenson-Roberts

Lin Wang ~ Urban Art & Antiques ~ June 9, 2014

Lin Wang ~ Urban Art & Antiques ~ June 9, 2014

It is easy to miss works by Carroll Swenson-Roberts. Many are done with color pencils, a medium often associated with childhood. With no bravura brush strokes nor oversized geometric abstraction, they don’t make viewers gravitate toward them, at the first glance. Instead, they tell personal stories. Bit by bit, only become captivating through time.

On the last Continental Gin Building Open Studio day, I found some small snippet works in watercolor stacked on a table. They looked incomplete, like some snapshot photos partially torn. The abstraction is due to her choice of leaving out the rest of her composition. Yet there is a kind particularity that seems to grow our curiosity. They are to be viewed as poems with few words, succinct and evocative. Emily Dickinson often wrote like that. (To make a prairie it takes a clover, and one bee). Swenson-Roberts’ small studies made me yearn for more.

And more it came.

The domestic genre paintings are ostensibly folkish and naïve looking. Yet it is no mistake that only a master hand could retain a stylistic naivety within a complex pictorial space, on a large scale.

On the last Continental Gin Building Open Studio day, I found some small snippet works in watercolor stacked on a table. They looked incomplete, like some snapshot photos partially torn. The abstraction is due to her choice of leaving out the rest of her composition. Yet there is a kind particularity that seems to grow our curiosity. They are to be viewed as poems with few words, succinct and evocative. Emily Dickinson often wrote like that. (To make a prairie it takes a clover, and one bee). Swenson-Roberts’ small studies made me yearn for more.

And more it came.

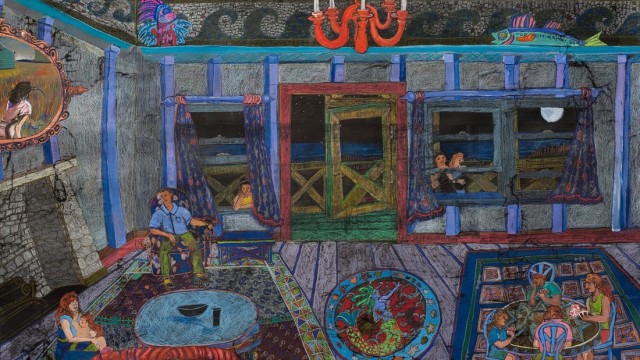

The domestic genre paintings are ostensibly folkish and naïve looking. Yet it is no mistake that only a master hand could retain a stylistic naivety within a complex pictorial space, on a large scale.

We observe the happenings from slightly above, like a spider on the ceiling. There is a tendency that different planes around the center are sloping downward, as if each room, regardless for living, dining or bathing, is one universe, around which that humans and their everyday objects must revolve.

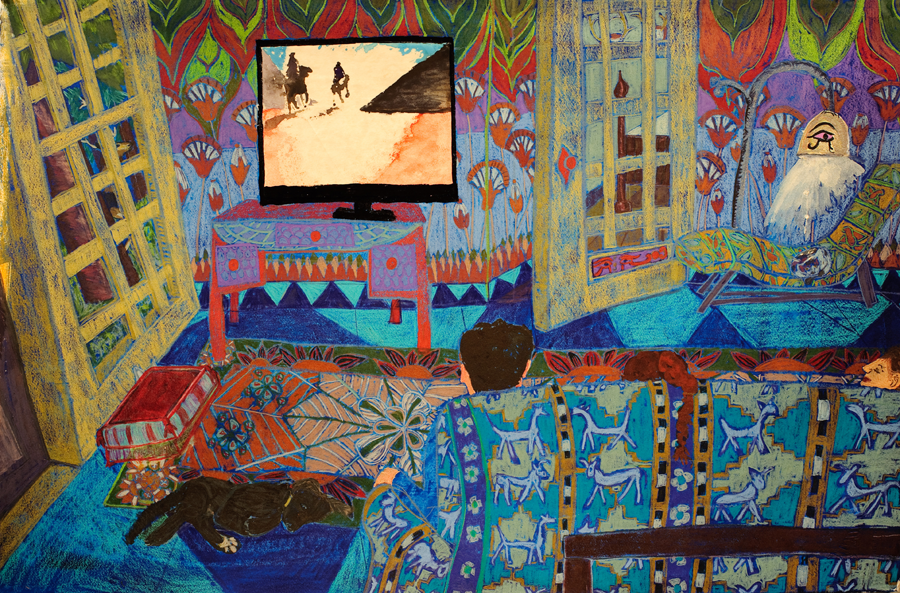

More looking reveals that there are maddening details meticulously and decoratively rendered. However, decorative is the means, not the goal. Intricate patterns, often interlocked within each other, dominate pictures. They are on the walls, in the carpet, or even from the frieze. It is hard to tell where memory merges into imagination. Be it the medieval deco in “The Family House,” or the Egyptian revival scheme in “Lawrence of Arabia,” they affirm that the happenings are told in a female voice. The mundane activity may be from reality, but a yearning for spicing up the ordinary transforms the space into an exotic wonderland, in her own mind.

To some extent, Swenson-Robert’s interior scenes share some similarity with memory paintings in their pursuit of minutia details of the past. However, while artists like Clara McDonald Williamson did portray domestic serenity, most of such works are aimed to provide a true reflection in great clarity (hence often in a unified well-illuminated daylight setting. Swenson-Robert injects factual-based stories with capricious imagination. In doing so, she is willing to let viewers drift around, within sections of rooms, and between actuality and her magic thinking.

The execution also differs. Instead of seeking perfect alignment, Swenson-Robert lets imperfect shapes and lines grow organically, retaining their whimsical intention. The aesthetic outcomes are fundamentally different. The tightly controlled compositions of memory paintings result from an unyielding vision of capturing the past. Swenson-Robert’s works project an air of care-free willfulness, which, to some extent, amounts to almost quixotic romanticism.

And they make you laugh too.

The artist keeps a painterly roughness on the surface by layering squiggling lines of opaque colors. The layering not only harmonizes a rather exotic palette (imagine the deep hued Egyptian blue), but also flattens imageries out of a fish-eyed perspective. Because of the similarity in both texture and chromaticity, small objects and humans are often hidden within larger furnishings. In “Lawrence of Arabia,” three persons sit on a sofa against the viewer. Their small heads almost disappear amid the overwhelming patterns of the fabric. And who would expect to see a dear behind the French door? Its absurdity caught me off guard when I first spotted it. Afterwards every peek of it reads like a funny comment that never grows stale.

More looking reveals that there are maddening details meticulously and decoratively rendered. However, decorative is the means, not the goal. Intricate patterns, often interlocked within each other, dominate pictures. They are on the walls, in the carpet, or even from the frieze. It is hard to tell where memory merges into imagination. Be it the medieval deco in “The Family House,” or the Egyptian revival scheme in “Lawrence of Arabia,” they affirm that the happenings are told in a female voice. The mundane activity may be from reality, but a yearning for spicing up the ordinary transforms the space into an exotic wonderland, in her own mind.

To some extent, Swenson-Robert’s interior scenes share some similarity with memory paintings in their pursuit of minutia details of the past. However, while artists like Clara McDonald Williamson did portray domestic serenity, most of such works are aimed to provide a true reflection in great clarity (hence often in a unified well-illuminated daylight setting. Swenson-Robert injects factual-based stories with capricious imagination. In doing so, she is willing to let viewers drift around, within sections of rooms, and between actuality and her magic thinking.

The execution also differs. Instead of seeking perfect alignment, Swenson-Robert lets imperfect shapes and lines grow organically, retaining their whimsical intention. The aesthetic outcomes are fundamentally different. The tightly controlled compositions of memory paintings result from an unyielding vision of capturing the past. Swenson-Robert’s works project an air of care-free willfulness, which, to some extent, amounts to almost quixotic romanticism.

And they make you laugh too.

The artist keeps a painterly roughness on the surface by layering squiggling lines of opaque colors. The layering not only harmonizes a rather exotic palette (imagine the deep hued Egyptian blue), but also flattens imageries out of a fish-eyed perspective. Because of the similarity in both texture and chromaticity, small objects and humans are often hidden within larger furnishings. In “Lawrence of Arabia,” three persons sit on a sofa against the viewer. Their small heads almost disappear amid the overwhelming patterns of the fabric. And who would expect to see a dear behind the French door? Its absurdity caught me off guard when I first spotted it. Afterwards every peek of it reads like a funny comment that never grows stale.

Displaying reproduction works of art by famous artists at home may sound low-brow. Incorporating them into another image adds a sense of humor. Works by Picasso, Wyeth and Caravaggio serve as a commentary that perhaps there is a desire of pursuing high art in every home.

In this sub-context oeuvre, “Lawrence of Arabia“ stands out in its genius adoption of pop culture imageries. Here the artist inserts a cut-out of a watercolor piece as the TV screen. The bright and un-muted watercolor demand our attention, even our eyes may drift around a room dominated in fanciful Egyptian deco. It is a movie that the family watch every year. A deer may have passed the door. People may have fallen into sleep on the couch. Yet the unflinching screen of Lawrence and his men on camels again pyramids are unequivocally epic and exotic. Apart from the gender inference, I see no difference, between an iconic silhouette from a classic movie and the imagined Re god light above the family cat, in their pursuit of a life larger than our own.

In this sub-context oeuvre, “Lawrence of Arabia“ stands out in its genius adoption of pop culture imageries. Here the artist inserts a cut-out of a watercolor piece as the TV screen. The bright and un-muted watercolor demand our attention, even our eyes may drift around a room dominated in fanciful Egyptian deco. It is a movie that the family watch every year. A deer may have passed the door. People may have fallen into sleep on the couch. Yet the unflinching screen of Lawrence and his men on camels again pyramids are unequivocally epic and exotic. Apart from the gender inference, I see no difference, between an iconic silhouette from a classic movie and the imagined Re god light above the family cat, in their pursuit of a life larger than our own.

|

Lin Wang

Lin Wang is the co-editor for Urban Art and Antiques. He believes words fail in both visual arts and music. Thus whatever he writes is just babbles, impulsive but irrelevant. |